Whether you are dealing with high rainfall or drought, a boggy site prone to flooding, or land that becomes parched and dry, managing water effectively and sustainably is crucial to long-term success.

If you have not thought much about water on your property then you are in a fortunate position. Increasing numbers are now having to think more carefully about water, and more and more people are going to have to think about it in future, even in areas where water is not presently a huge concern.

I am very fortunate to live in an area that is relatively water secure and experiences few extremes. But even here we are seeing more incidences of low-water periods and near-drought conditions in spring, more storms, and road flooding during wetter periods of the year.

Through my work, I also see an increase in the number of clients who are concerned about water in one way or another, from many different parts of the world. If you would like help to manage water sustainably where you live, please contact me to discuss your location, project scope, and goals.

Sustainable Water Management – A Starting Point for Design

In permaculture design, water is of course one of the first elements we look at when assessing a site. Water is life – and how it moves, is stored, and used on a property can have ripple effects through the entire system. Sustainable water management begins with observation. We must understand how water behaves on our land before we intervene.

Look for clues. Where does water enter and leave your site? Where does it collect or pool? What happens during a heavy downpour? What dries out first in a dry spell? What plants are already thriving? These observations offer valuable insights, allowing us to work with what we have rather than forcing a system upon the land.

Climate & Location Appropriate Landscape Design

Designing a system suited to your specific climate and site is key. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. In wetter temperate climates, the focus may be on slowing water down and moving it away from areas where it might cause harm. In arid climates, we focus on harvesting every drop and keeping it on site for as long as possible.

It’s important to understand not only annual rainfall averages but also seasonal distribution. For example, in the UK, we often receive the bulk of our rainfall in autumn and winter, while springs can be surprisingly dry. Designing for these patterns – and the increasing irregularity of those patterns – is now essential.

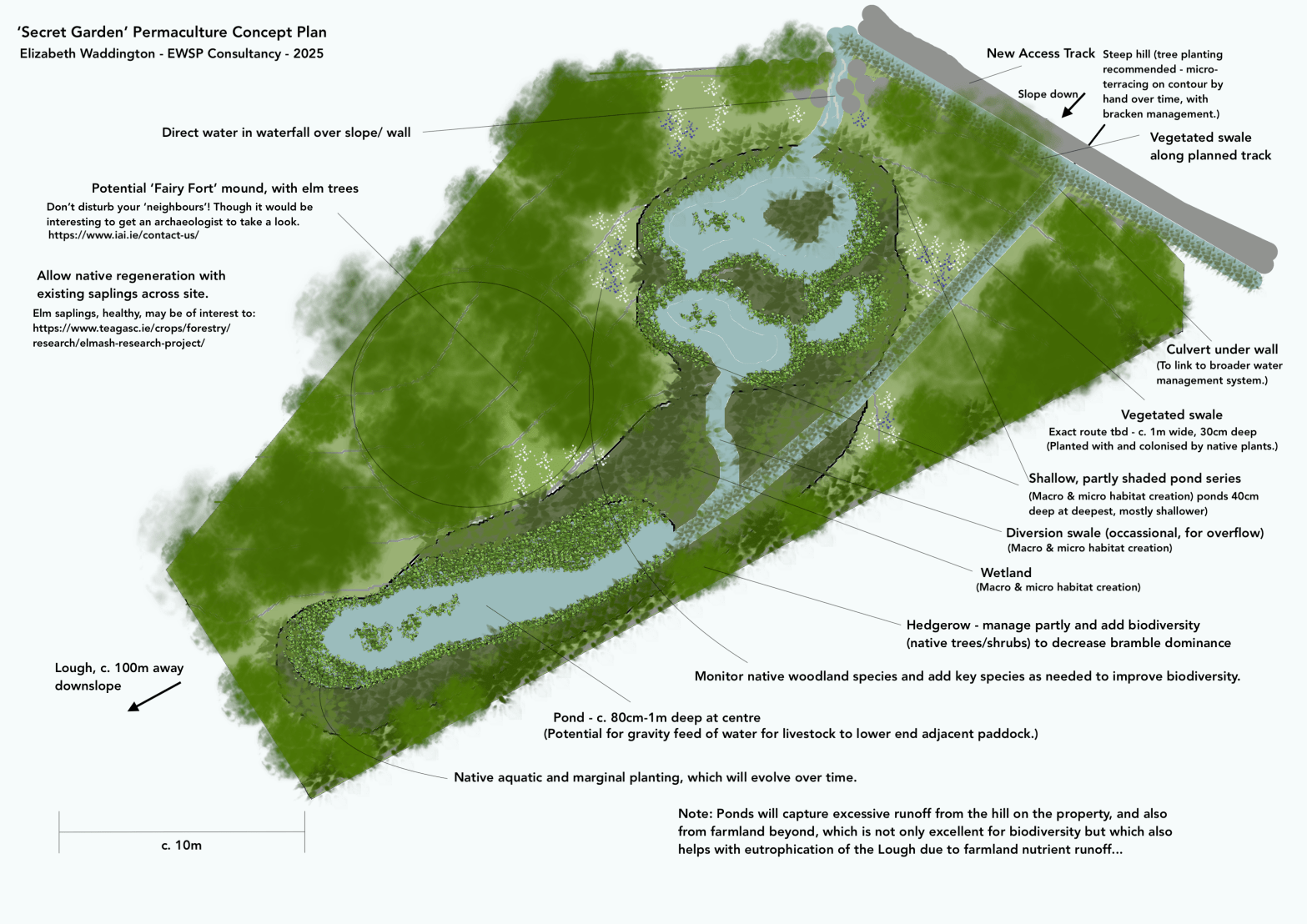

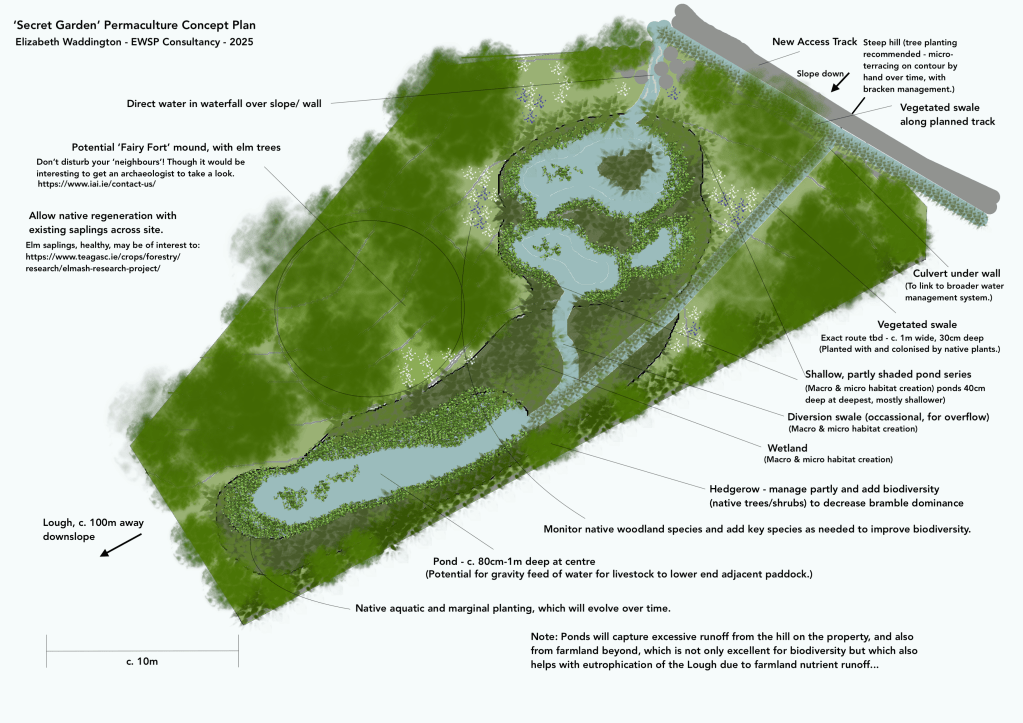

In practice, this might mean shaping the land to follow contour lines, creating swales or bunds, integrating ponds, or even rewilding certain areas to restore natural hydrological functions.

Managing Water Shortage

Periods of water scarcity are increasingly common, even in traditionally wet regions. Drought resilience is no longer a concern limited to Mediterranean climates or semi-arid landscapes. We all need to be thinking about how to make our systems more robust.

One of the best ways to do this is by improving soil health. Soils rich in organic matter hold water like a sponge, reducing the need for irrigation. Mulching, no-dig methods, and integrating perennial planting systems can all build soil that is more resilient in dry spells.

Another key strategy is reducing the water needs of the system as a whole. Lawns, for example, are water-thirsty and offer little ecological value. Replacing them with native wildflower meadows, edible perennials, or mixed polycultures can make the land both more productive and more drought-tolerant.

Catching & Storing Water

In permaculture, we are fond of the phrase: “slow it, spread it, sink it.” This principle guides our approach to water harvesting. Wherever possible, we seek to catch and store water – in the soil, in plants, and in containers – so it is available when needed.

Rainwater harvesting systems are often the first step. A simple rain barrel can be a good start, but I encourage clients to think bigger where possible – especially if water access is precarious. Tanks connected to guttering from roofs can collect thousands of litres annually. Even sheds and greenhouses can be part of this system.

Larger landscape interventions, such as ponds and swales, can play a significant role too. Swales – shallow ditches dug on contour – capture rainwater and allow it to slowly infiltrate the soil rather than running off. Ponds, if appropriately designed, can store surplus water and support biodiversity, creating habitat for frogs, dragonflies, and more…

Water Conservation

Conserving the water we already have is just as important as catching more of it. Irrigation is often where the most waste occurs, particularly in summer gardens. Thoughtful planting, timed irrigation, and smart design can reduce this dramatically.

Planting in guilds or layers, as we do in forest gardens, creates a microclimate that retains moisture. Using shade-tolerant ground covers can reduce evaporation. Drip irrigation systems are much more efficient than hosepipes or sprinklers, as they deliver water directly to the root zone.

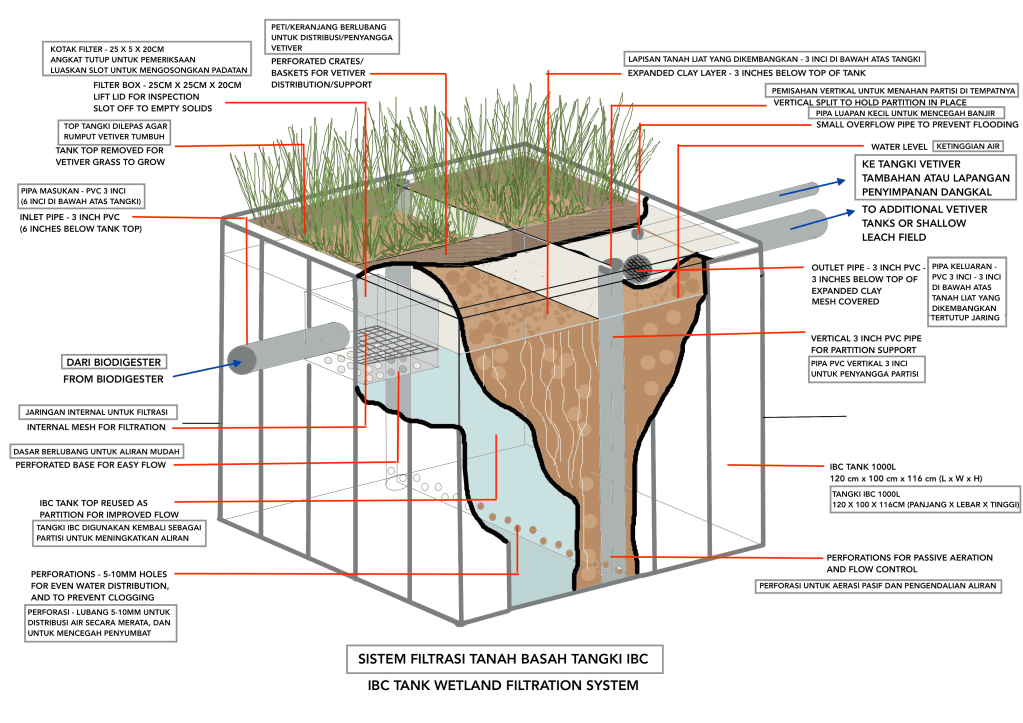

When we use water, we must do so consciously. Avoid watering during the heat of the day. Direct greywater from sinks or showers (using appropriate filters and soaps) to irrigate ornamental plants or fruit trees. Even modest changes like these can reduce demand on mains water dramatically.

Managing Excess Water

Increased rainfall and storm events are becoming more common in many areas. Rather than seeing this excess water as a problem, however, we can often find ways to put it to good use by working with nature, and by carefully redirecting it where it causes problems.

This may involve increasing drainage in compacted soils, using French drains or deep mulching. In some cases, you may need to channel water away from structures or paths. However, rather than piping it straight off site, we aim to redirect it into areas that can benefit – such as wildlife zones, rehydrated woodlands, or ponds.

Creating wetlands or rain gardens can be a wonderful way to capture water and support wildlife at the same time. These areas act like natural sponges, holding water during peak flows and slowly releasing it back into the system.

We can also take advantage of these properties to find sustainable ways to deal with waste water.

Working With Nature

Nature offers many solutions when it comes to water management. Trees, for instance, are some of the most powerful tools we have. Their deep roots improve soil structure, their canopies reduce evaporation, and their presence encourages more stable microclimates.

Wetlands, ponds, riparian buffer zones, and forested areas all play roles in natural hydrological cycles. When we mimic these systems in our designs, we often find that they are more resilient, more productive, and more beautiful as a result.

Rather than controlling water, we aim to cooperate with it. Remembering that co-operation is key is very important on any permaculture property.

A series of small, shallow, shaded ponds and wetland zones through this area belonging to clients in Ireland can not

only help with water management and help to reduce eutrophication of the nearby Lough due to

agricultural runoff, but can also significantly boost biodiversity in this area.

Redirecting Water

Water always moves – and understanding and directing this movement is part of our role as designers. Through careful planning, we can ensure that water is redirected in ways that support abundance rather than causing damage.

A well-placed swale, a diversion trench, or even a series of well-contoured beds can make the difference between water that nourishes and water that erodes. Observing slope, flow, and seasonal patterns allows us to shape the land in gentle ways that guide water where it can do the most good.

Whether you’re working a small garden or a large piece of land, now is the time to begin thinking carefully about water.

If you need support developing a water-wise system where you live, I would be delighted to hear from you.